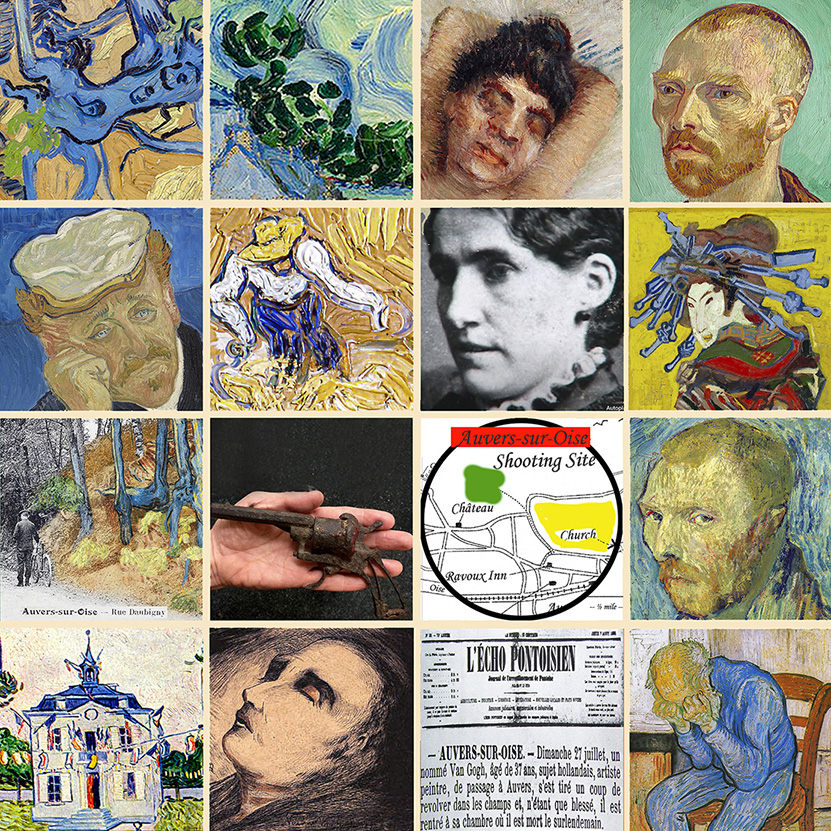

There are many different stories about the death of Vincent van Gogh, including a 300 page book with "made-up" forensic evidence about "his murder", a book produced by some American. And here we come with our story and our UNIQUE PROVES... So enjoy....

In the weeks before his suicide Vincent van Gogh made three paintings

with clearly explicit details that were pointing to his nearing death. With these three paintings he expressed what he didn't want or couldn't

scream out to the world around him. In secret Vincent painted his three

"Harbingers of his death". I'll write here about other paintings as well with vague hints about his suicide-plans and about Vincent losing his faith and hope in life.

As far as we can find, however the three paintings mentioned here below have clearly their straight focus on "death".

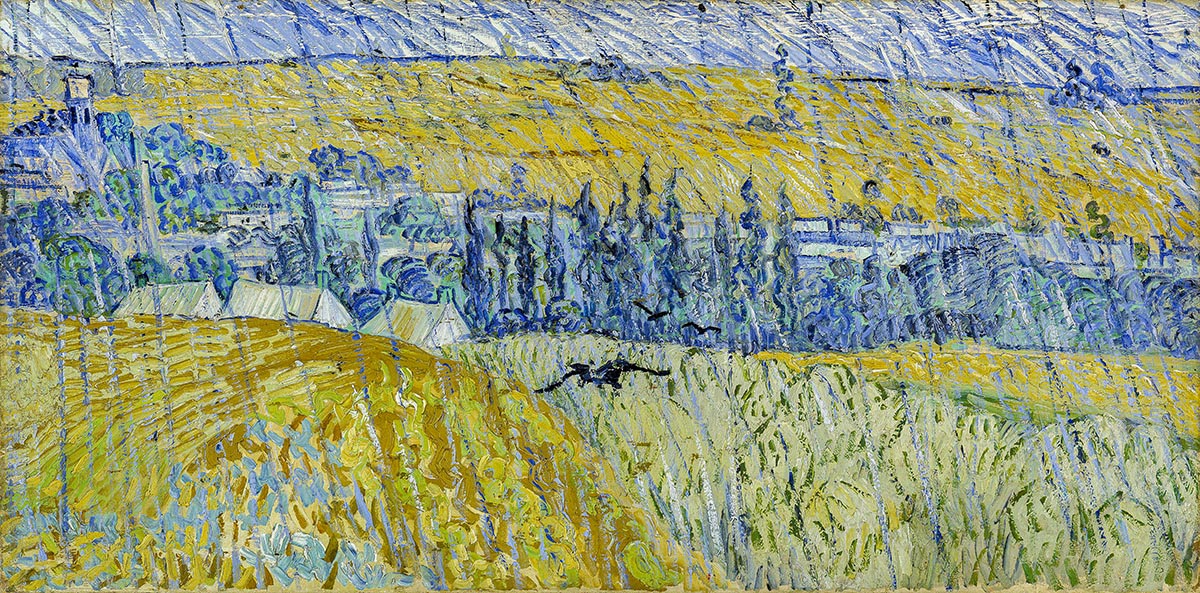

(1) He made "Towards Heaven" (official name is: Wheat Fields with Reaper).

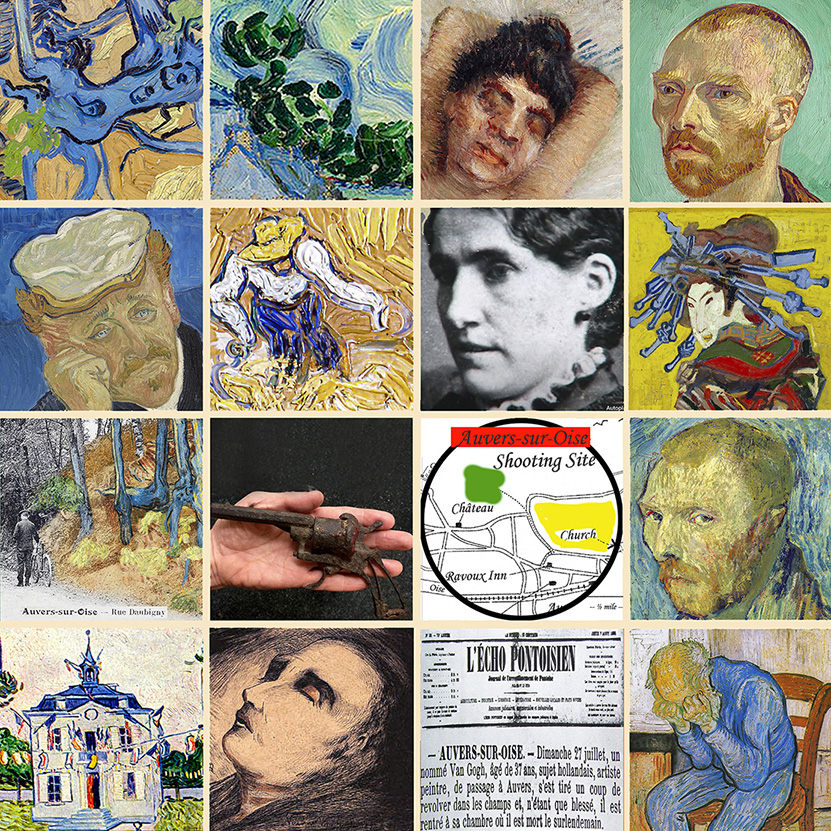

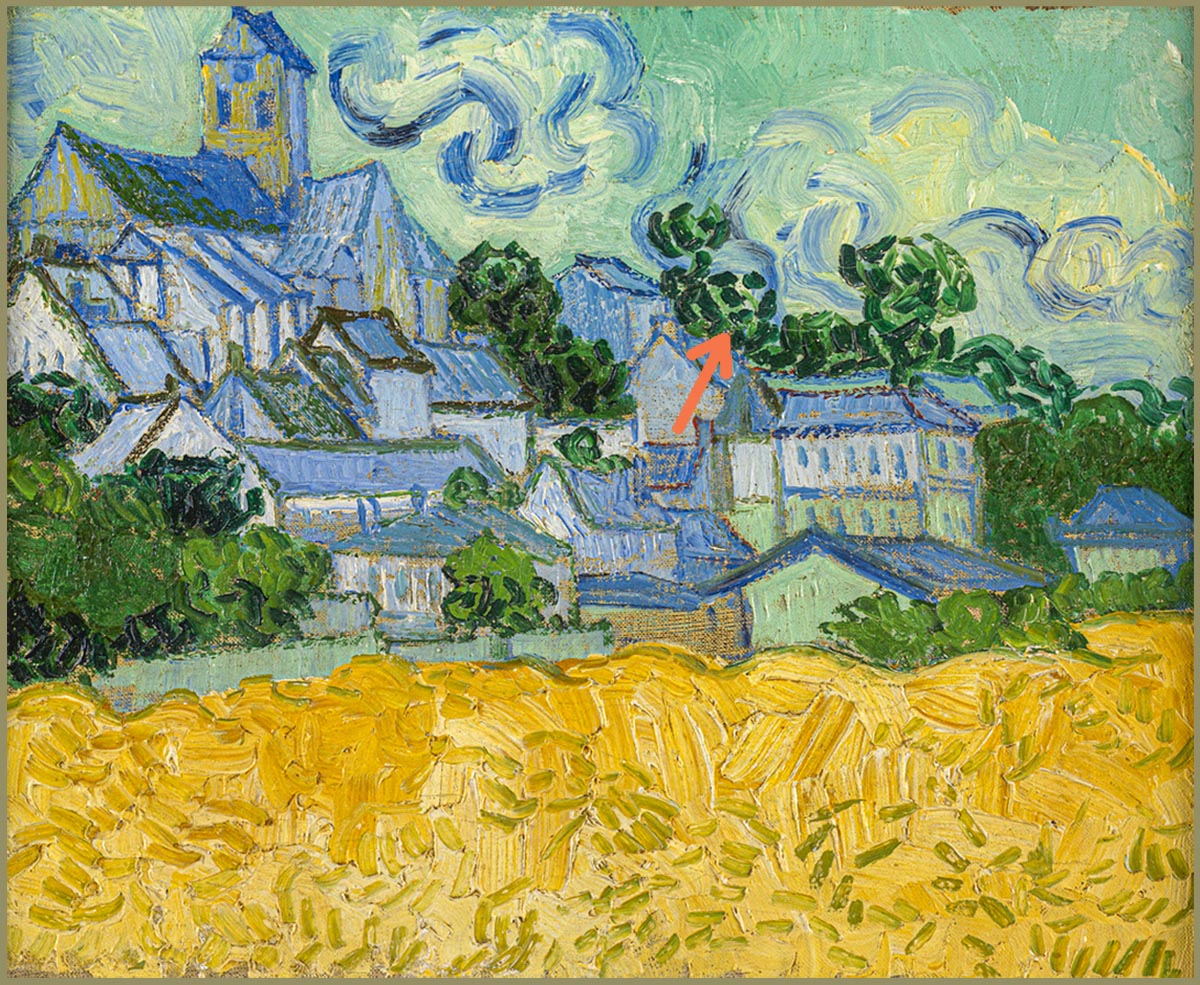

(2) Shortly after this, he painted the "Skull in the trees watching over the field of execution." (official name: "View on Auvers with Church" at present in Rode-Island Museum USA).

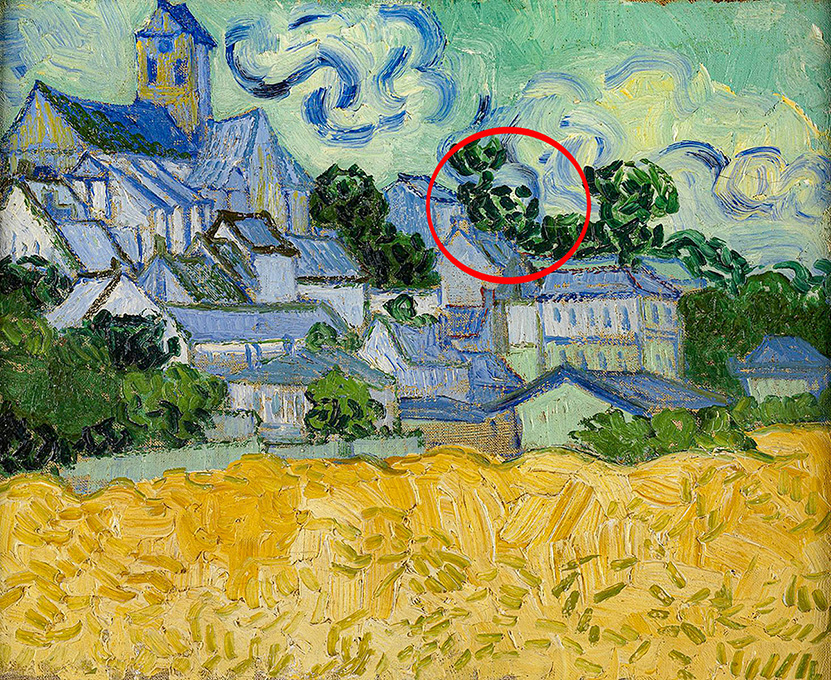

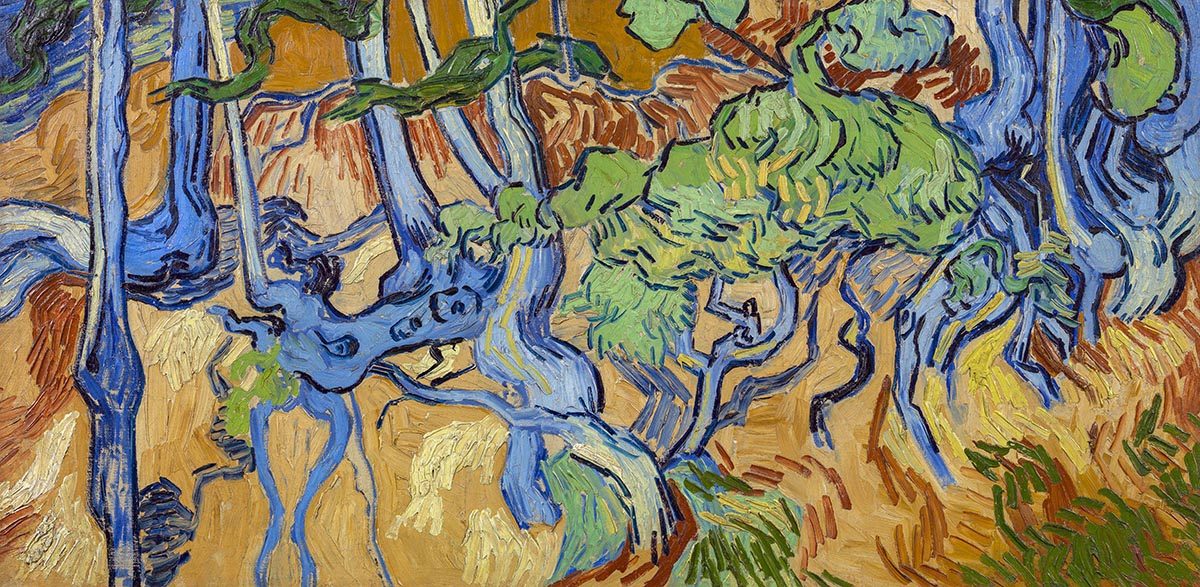

(3) With the "TreeRoots" he finally terminated his "trilogy of death" on the 27th of July 1890; he painted this work on the very day

of his suicide attempt and only a few hours before he shot himself in his chest in the field behind the castle in Auvers-sur-Oise.

You'll read in our story how Vincent van Gogh expressed in his final paintings what he

secretly felt and planned and what he couldn't speak out. And how and why he

prepared himself to depart from this life on earth at an age of just 37 years.

Our storyline and interpretations are unique and the socalled "van Gogh-scholars" never

commented on our view.

It sure looks like Vincent did a well thought out and premeditated suicide. Read here and judge for yourself!!

Further in our report here I'll try to analyze how this gifted and well educated young man from a good family from the south of the Netherlands became such an astounding failure during his lifetime. It was only because of the yearslong and relentless efforts and prudent business management of his sister-in-law, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, that Vincent could reach the stardom he posthumously achieved. Mrs Jo Bonger deserves the spotlight in this great succes. Many insiders believe that without her we would never even have heard about Vincent van Gogh at all !! Here below a painting of mrs Jo Bonger by dutch painter Isaac Israëls.

We do have our unique interpretations of his paintings (as well as of his character) and our analyses are based on a long study of van Gogh's paintings and letters. We've found details in his paintings that nobody ever NEVER noticed in the 130 years that passed till today.

Reaper Vincent with two (2) reaper knives on his way to the white field in the distance.... this white field looks like a cloudy magic carpet that will carry him to heaven. Van Gogh never painted white fields.... the fields that he painted were always yellow, green, brown.... never white...

Reaper Vincent with two (2) reaper knives on his way to the white field in the distance.... this white field looks like a cloudy magic carpet that will carry him to heaven. Van Gogh never painted white fields.... the fields that he painted were always yellow, green, brown.... never white...

He is escorted by a line of honor in military colors. See the clouds that are descending and impatiently waiting to carry him into heaven. In the upper right sky Vincent painted a "paved road"...... into heaven or towards... only God knows...

He is escorted by a line of honor in military colors. See the clouds that are descending and impatiently waiting to carry him into heaven. In the upper right sky Vincent painted a "paved road"...... into heaven or towards... only God knows...

Reaper Vincent has two (2) reaper knives and that is very rare... a farmer normally carries only one reaper knife while working in the field.... So.... this reaper is NOT reaping here.... Vincent is on his way to heaven and death!

Reaper Vincent has two (2) reaper knives and that is very rare... a farmer normally carries only one reaper knife while working in the field.... So.... this reaper is NOT reaping here.... Vincent is on his way to heaven and death!

Thousands have been "seriously studying" the famous painter van Gogh. It appears a bit unbelievable that in all of the 130 years that passed, nobody ever noticed this skull in the trees. We should be proud of our discovery... of... "our skull". Apparently the skull has a low-hanging ear, while some laughing angels are flying around.... This skull is overlooking the very cornfield in front of the castle. Here it should happen... that seemed to be Vincent's plan.

You don't need a lot of imagination to see the skull in the trees.

You don't need a lot of imagination to see the skull in the trees.

Coincidently for over 130 years nobody did recognize this head of death in these "not-so-random brush strokes" of Vincent. We asked the owner of this painting, a museum in Rhode-Island (USA).... They wrote to us that they never heard of or noticed this.

Coincidently for over 130 years nobody did recognize this head of death in these "not-so-random brush strokes" of Vincent. We asked the owner of this painting, a museum in Rhode-Island (USA).... They wrote to us that they never heard of or noticed this.

And it happened...

Back to his roots; a few hours after painting this big "TreeRoots" canvas (50x100 cm), he fatally shot himself in his chest and layed himself to rest between his roots, as he showed us in this final painting.

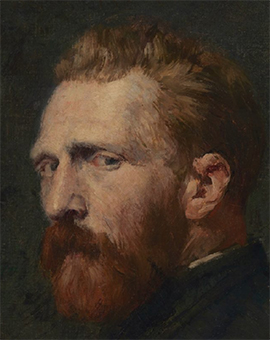

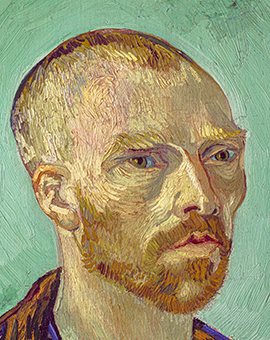

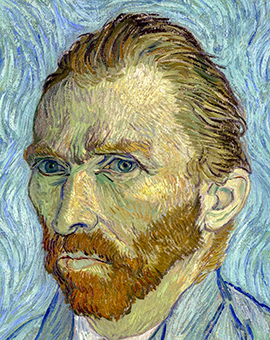

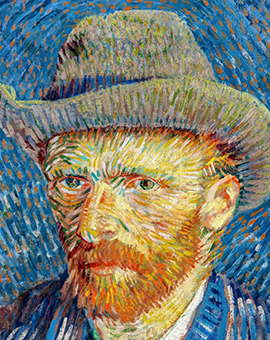

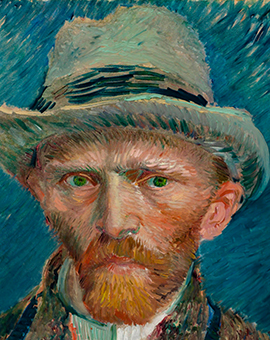

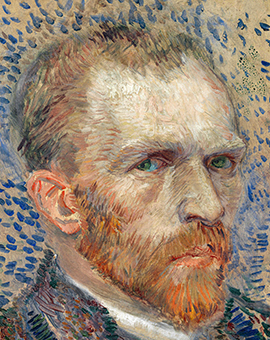

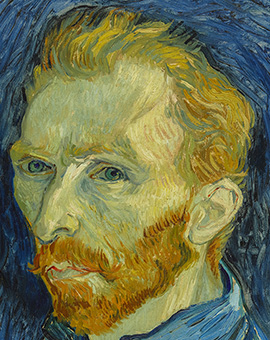

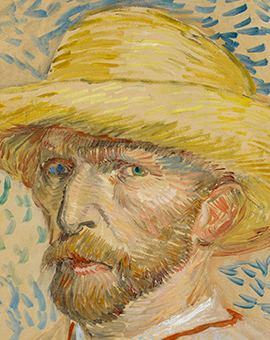

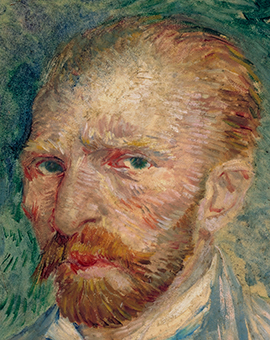

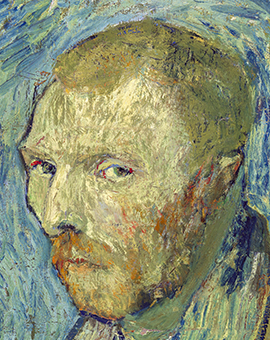

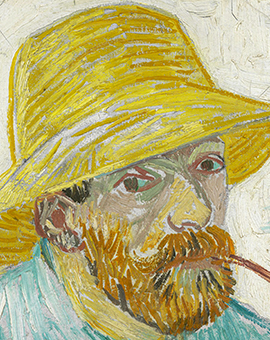

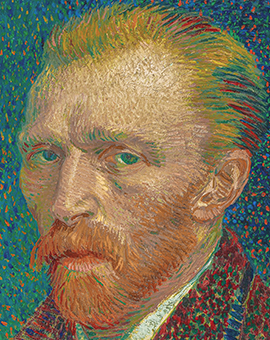

Here below first some more portraits of van Vincent

van Gogh.

Click in each one for a bigger picture....

|

|

|  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below: one of the most iconic paintings of Vincent: Starry

Night (1889).

Click for a bigger Starry Night

Over the years the death of Vincent has been the subject

of many

fantastic stories, published in books, movies,

publications and websites.

However, in recent years there have been made various new discoveries regarding the last months of his life in the French village Auvers-sur-Oise:

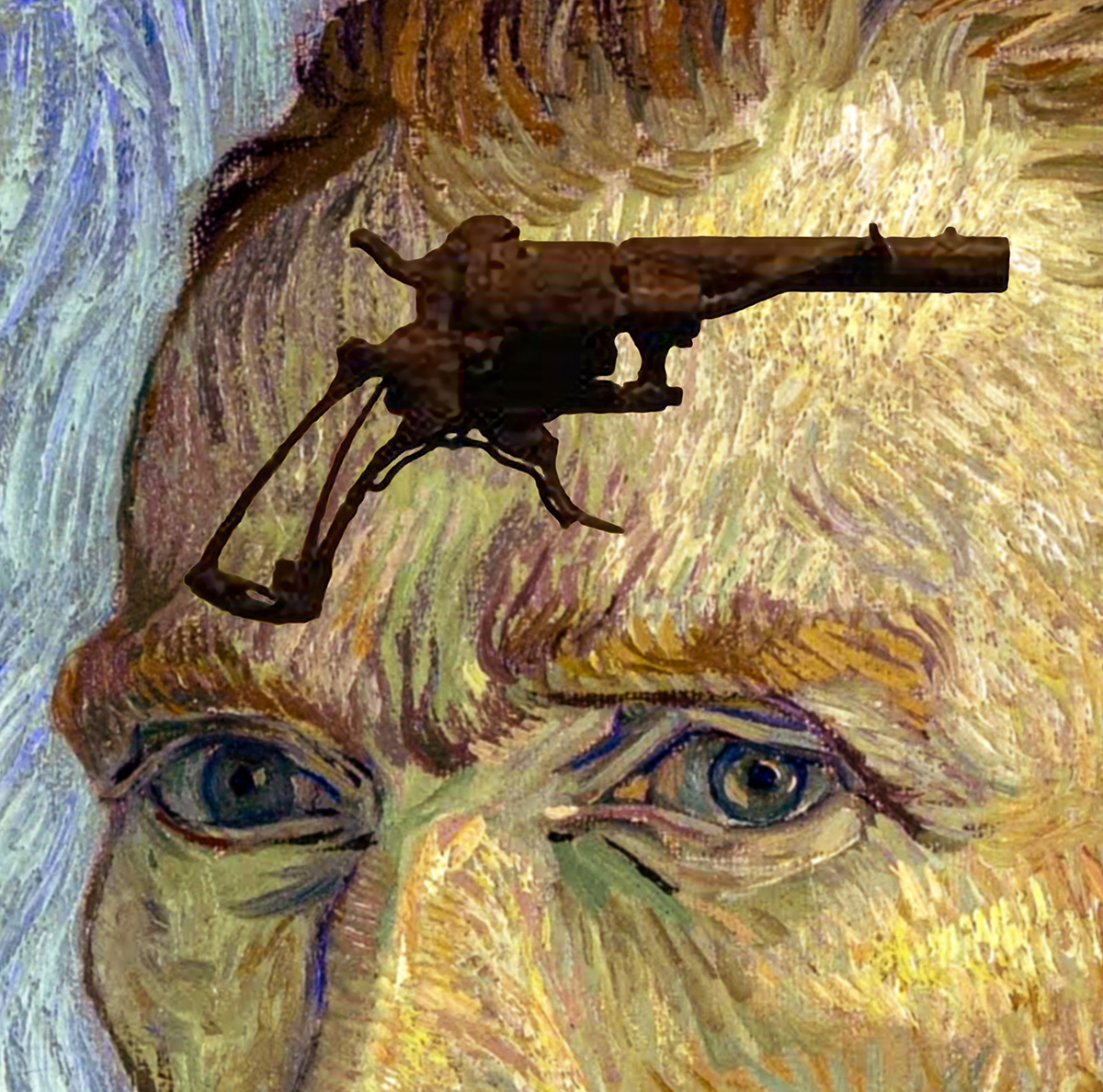

+++The discovery of the gun in 1960.

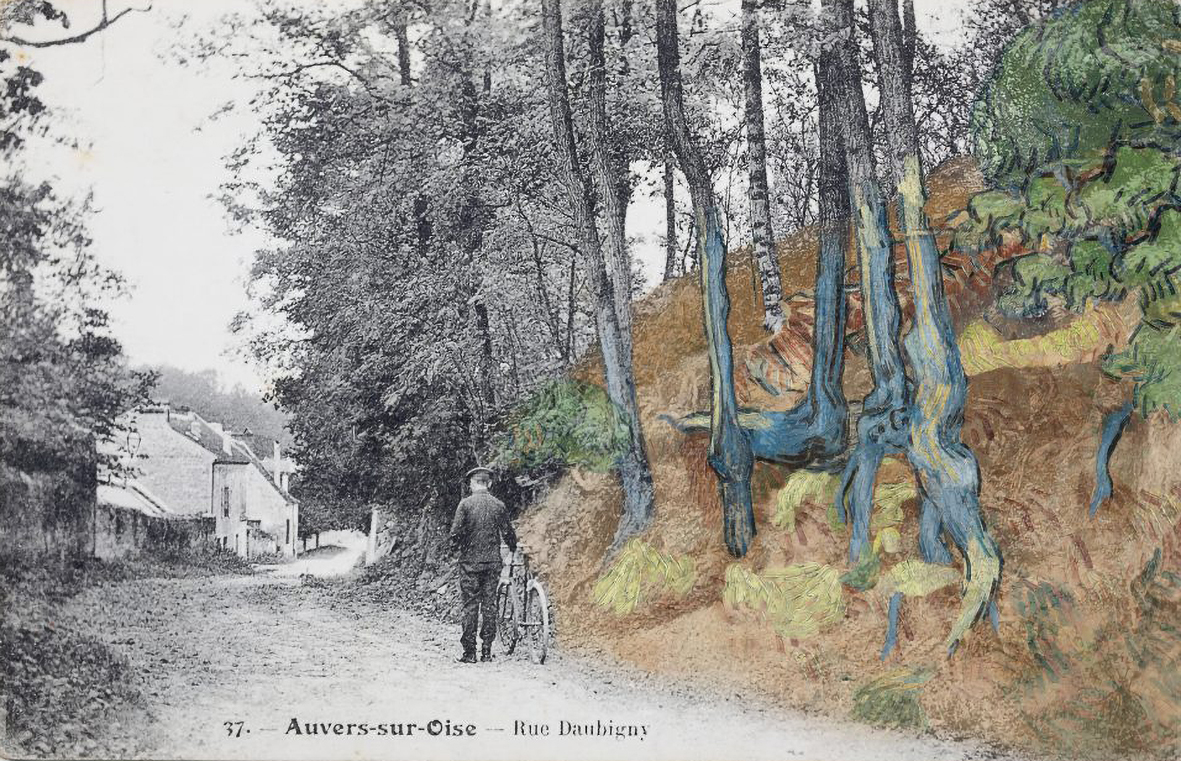

+++The original location of the painting "TreeRoots" by Wouter van der Veen in 2021 and the statement of the confirmation that TreeRoots was the last painting of van Gogh.

+++Last but not least is our own discoveries in early 2021 of the skull in the trees in the painting "View at Auvers with Church" and the

two reaper knives in van Gogh's painting in the Toledo Museum.

These recent

findings are supporting the latest and "most truthful

representations" of

what happened in June and July 1890 in Auvers-sur-Oise and what led to the death of Vincent van Gogh. Our story is based on the analyses of Vincent's paintings and letters, as well as on publications among others of Van Gogh Museum A'dam,

Martin Bailey, Wouter van der Veen and various publications

on the web. You'll understand that the story of "the murder of Vincent van Gogh" is not viable and realistic anymore after these latest discoveries.

We'll try to avoid dreaming on the cult around van Gogh

and his socalled "famous brusstrokes". He deserves better... there was a lot

of deep understanding in his mindfull decisions... and we will try to penetrate into the mind of this clever and complex personality and we will point at various

details in his paintings that can't be coincidences.

We'll analyze

ten significant

paintings that all were painted in the very weeks before his suicide in

Auvers-sur-Oise. These ten paintings contain hidden secret messages that Vincent was trying to convey.... he was more a painter than a writer.... He wrote to Theo in July:

We'll analyze

ten significant

paintings that all were painted in the very weeks before his suicide in

Auvers-sur-Oise. These ten paintings contain hidden secret messages that Vincent was trying to convey.... he was more a painter than a writer.... He wrote to Theo in July:

"So - having arrived back here, I have set to work again - although the brush is almost falling from my fingers - and because I knew exactly what I wanted to do, I have painted three more large canvases. They are vast stretches of corn under troubled skies, and I did not have to go out of my way very much in order to try to express sadness and extreme loneliness. I hope you will be seeing them soon since I'd like to bring them to you in Paris as soon as possible. I'm fairly sure that these canvases will tell you what I cannot say in words, that is, how healthy and invigorating I find the countryside."

Van Gogh was not deranged. Yes, he had his moments. But his paintings were a product of serious practice and artistic development, because he was extremely sensitive, devoted, and lucid whenever he was well enough to paint.

In May of 1890 the late Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh was

released

from the asylum in Saint Remy (France), where he

"voluntary" but

pressed by his brother Theo, had spent one year and where

he

painted a part of his most famous works like Starry

Night (see above),

Almond

Blossom, the Irisses.  Van Gogh's "terrifying environment" of this french asylum

is revealed

exclusive in a book of Martin Bailey, describing the

harrowing period

in which he produced his most beloved works. The author

and

journalist Martin Bailey, an expert on van Gogh’s life,

traced the

admissions register and other records from Saint-Paul de

Mausole,

a small asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence,

for the

period when Van Gogh was admitted as a private patient, a

stay paid

for by his brother Theo. The register shows Vincent van

Gogh, 36,

from Arles but born in the Netherlands, was admitted on 8

May 1889.

Van Gogh's "terrifying environment" of this french asylum

is revealed

exclusive in a book of Martin Bailey, describing the

harrowing period

in which he produced his most beloved works. The author

and

journalist Martin Bailey, an expert on van Gogh’s life,

traced the

admissions register and other records from Saint-Paul de

Mausole,

a small asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence,

for the

period when Van Gogh was admitted as a private patient, a

stay paid

for by his brother Theo. The register shows Vincent van

Gogh, 36,

from Arles but born in the Netherlands, was admitted on 8

May 1889.

Through the register, Bailey traced the 18 male patients

including an

elderly priest, Jean Revello, and Henri Enrico, who was

described as

constantly smashing up furniture and crockery. Van Gogh

described

fellow patients, whom he called “my companions in

misfortune”,

slumped into silent resignation, with no treatment and

nothing to fill their

days except the next stodgy meal, eaten with a spoon

because of the

risk from knives and forks. Some, however, were very

troubled. In one

letter, he described the long nights: “One continually

hears shouts and

terrible howls as of animals in a menagerie.”

Through the register, Bailey traced the 18 male patients

including an

elderly priest, Jean Revello, and Henri Enrico, who was

described as

constantly smashing up furniture and crockery. Van Gogh

described

fellow patients, whom he called “my companions in

misfortune”,

slumped into silent resignation, with no treatment and

nothing to fill their

days except the next stodgy meal, eaten with a spoon

because of the

risk from knives and forks. Some, however, were very

troubled. In one

letter, he described the long nights: “One continually

hears shouts and

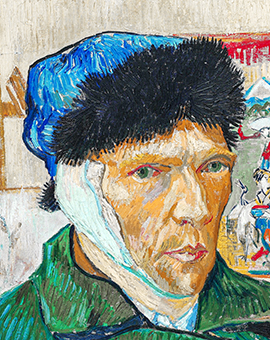

terrible howls as of animals in a menagerie.” Vincent was judged by his brother and friends to be unfit

to live alone

after he mutilated himself, cutting off his ear

and presenting it, wrapped

in paper, to a young woman in a local brothel, following

the collapse of a

proposed artistic partnership with his companion Paul

Gauguin. The

register was key to discovering previously unknown details

of the artist’s

time there, including the fact that neither his friends

from Arles, 16 miles

(25km) away, nor Theo (his brother and best friend) ever

visited.

Theo van Gogh was kept informed by the stream of

illustrated letters

from his brother, but also news from the asylum director

of van Gogh’s

three serious collapses over the year, when the paints he

tried to

swallow had to be taken from him, and he was confined to a

small, bare,

locked room instead of his usual bright bedroom and

separate studio on

an upper floor. The director of the asylum, Théophile

Peyron, wrote:

“On several occasions he has attempted to poison himself,

either by

swallowing colours that he used for painting, or by

ingesting paraffin,

which he had taken from the boy while he was filling his

lamps.

” His brother, recently married and expecting his first

child in Paris,

stayed away. Bailey wrote: “I now appreciate quite what a

terrifying

environment it must have been for van Gogh."

“That makes it even more astonishing that he was able to

create some of

his finest and [most] optimistic paintings in such a

situation. I am also

convinced that it was his art which enabled him to

survive.”

Vincent was released on 16 May 1890, at his own request,

despite

evidence of mental collapse following his previous brief

breaks from the

asylum. He yearned for new spring landscapes to paint,

blamed the

company of his fellow patients for his previous and

longest collapse, and wrote “the prison was crushing me”. Here below first a

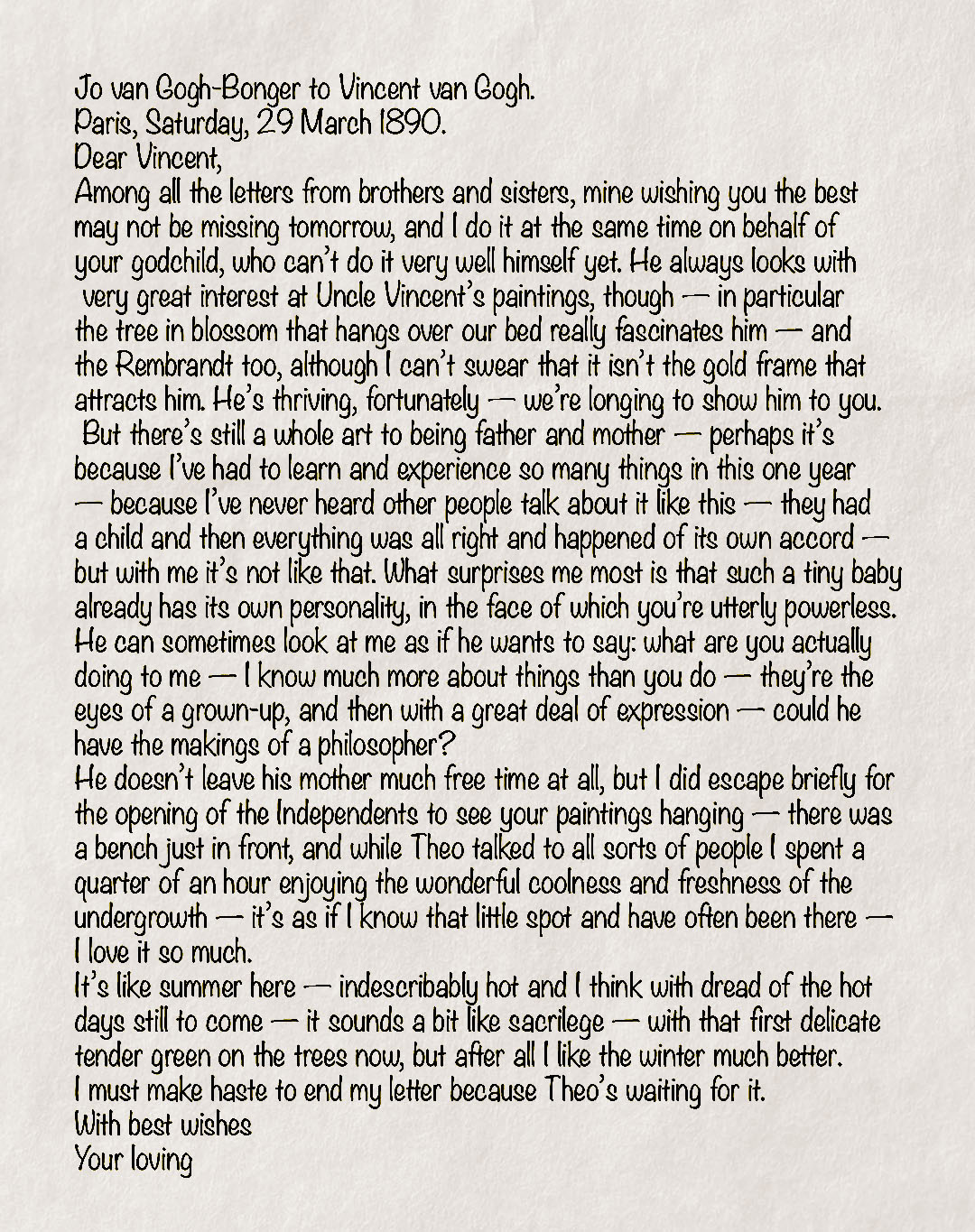

letter, written by Theo's wife Jo a few weeks

before Vincent is leaving the asylum...

Vincent was judged by his brother and friends to be unfit

to live alone

after he mutilated himself, cutting off his ear

and presenting it, wrapped

in paper, to a young woman in a local brothel, following

the collapse of a

proposed artistic partnership with his companion Paul

Gauguin. The

register was key to discovering previously unknown details

of the artist’s

time there, including the fact that neither his friends

from Arles, 16 miles

(25km) away, nor Theo (his brother and best friend) ever

visited.

Theo van Gogh was kept informed by the stream of

illustrated letters

from his brother, but also news from the asylum director

of van Gogh’s

three serious collapses over the year, when the paints he

tried to

swallow had to be taken from him, and he was confined to a

small, bare,

locked room instead of his usual bright bedroom and

separate studio on

an upper floor. The director of the asylum, Théophile

Peyron, wrote:

“On several occasions he has attempted to poison himself,

either by

swallowing colours that he used for painting, or by

ingesting paraffin,

which he had taken from the boy while he was filling his

lamps.

” His brother, recently married and expecting his first

child in Paris,

stayed away. Bailey wrote: “I now appreciate quite what a

terrifying

environment it must have been for van Gogh."

“That makes it even more astonishing that he was able to

create some of

his finest and [most] optimistic paintings in such a

situation. I am also

convinced that it was his art which enabled him to

survive.”

Vincent was released on 16 May 1890, at his own request,

despite

evidence of mental collapse following his previous brief

breaks from the

asylum. He yearned for new spring landscapes to paint,

blamed the

company of his fellow patients for his previous and

longest collapse, and wrote “the prison was crushing me”. Here below first a

letter, written by Theo's wife Jo a few weeks

before Vincent is leaving the asylum...

Vincent moved via Paris, where his brother Theo was living

with

his family, to the small village of Auvers-sur-Oise, 25

kilometers

more to the north in France. He had hoped to find peace of

mind here and he had hoped to be able to continue his work

as

an art-painter.

However, all went different in Auvers as our dear Vincent

had

too many personal problems.

To mention a few:

- Vincent permanently felt the threat of losing the

essential and vital financial support of his brother Theo.

Vincent understood that his brother had advanced syphilis while Theo

just got married, he had a babyboy and wanted to start his own

art-business with all financial uncertenties. Vincent could become a

burden...

- Vincent was aware of his own very bad health as a result

of his yearslong syphilis as well as and working with (and

sometimes eating) the poisonous paints and drinking

turpentine, while trying to end his life on various occasions in the recent

past. He was

as well worried that his glaucoma would result in

blindness...

- He suffered from an extreme loneliness as his difficult

character pushed away any possible friend, companion or

lover, while he needed so badly whomever at his side... He often

felt socially rejected by persons around him.... he was extremely

insecure.

- Vincent didn't have a clear straigthforward contact with

the persons around him.... he had different

personality-presentations for each individual around him..... he was a

typical vague guy from Brabant, the south of the Netherlands.

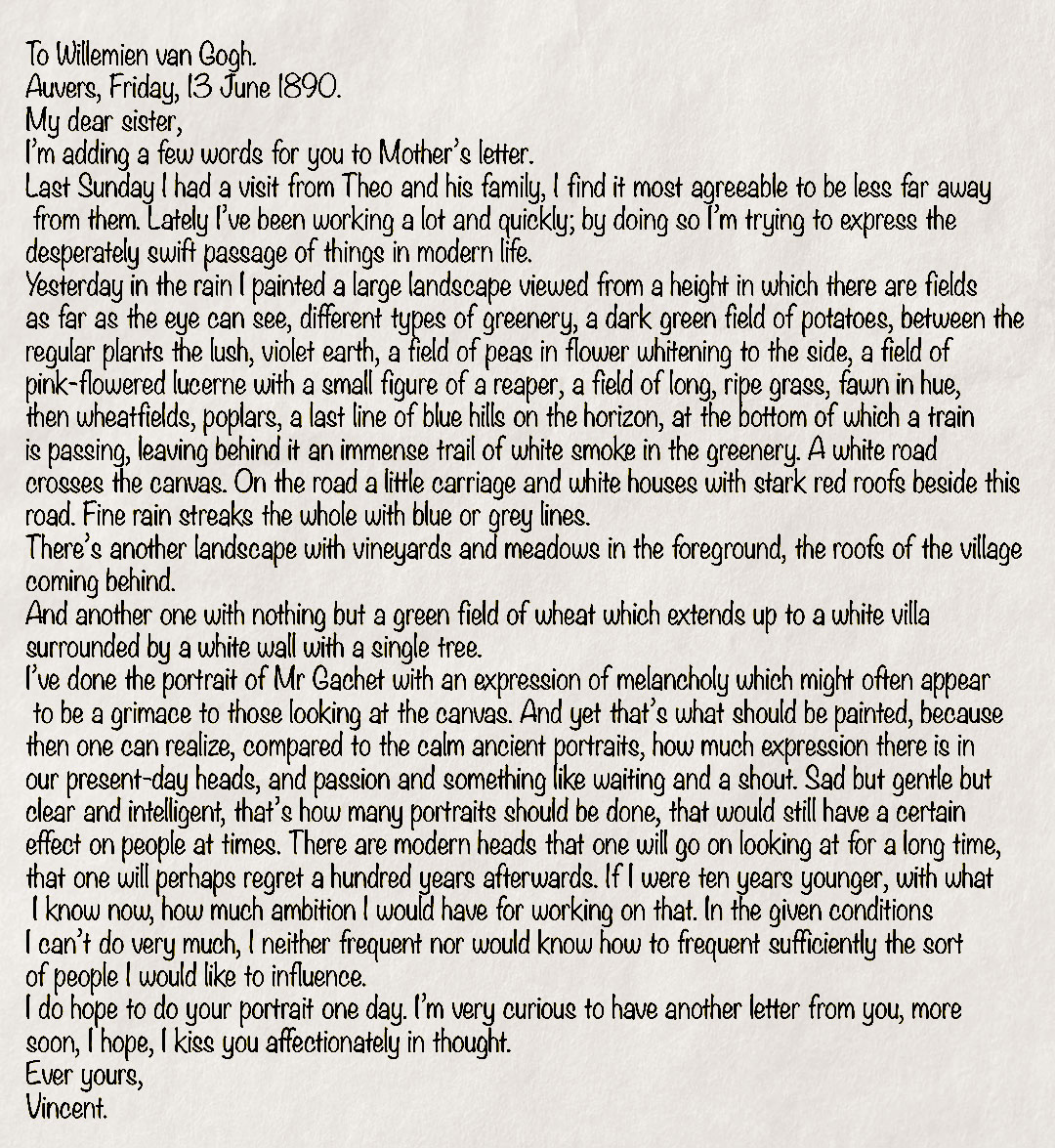

An example of this caracter may be seen in the following

letter that

Vincent wrote to his sister in June 1890.... while he was

entering the

utmost crisis of his life and living towards his

suicide.... He wrote this

very calm and non-alarming letter in which all seemed to

be all-right:

a simple letter, proving that Vincent was far from the

madman that

many people believe he was.... He just had his ups and downs....

Vincents ability to paint beautiful art depended on his state of mind

and his social tranquility. In the asylum in Saint Remy,

separated from

social disturbancies, van Gogh made his best works. However, now in Auvers, there were lots of derailing influences that he had to

overcome to reach an acceptable artistic level... In Arles he had had the strong hope of having his

"illusion Studio of the South" while he had the girls

in this big town... Than came Paul Gauguin with the disasterous

outcome as this guy was an egocentric artist and not a suitable

socially caring person that Vincent needed. After only two months this resulted in a

cut-off ear and Vincent going to an asylum. Vincent stayed a full year in Saint-Paul Asylum in Saint-Rémy de

Provence where his social force didn't improve while he appeared

to recover from the mental blow of the departure of

Gauguin.

Anyway he left Saint Rémy in May 1890 but the entry into the real

world

after one year in relative isolation turned

out to be

far too overwhelming for this over-sensitive vulnerable

creature....

In Paris he was happy to see Theo's son Vincent for the

first time.

However, the social intensity in Paris got, after only two

days, too much to bear and he had an early escape from Paris to

Auvers-sur-Oise, where he was planned to stay "under guidance" of

Paul Gachet, a homeopathic doctor and art-collectioner. Gachet, himself a

complex and busy personality, never digged deep into the

psyche of Vincent nor gave him any relaxing herbs...

Gachet put him up to

simply paint. Vincent anyway felt some kind of help and friendship

while he was trying to find an equilibrium in his mind while painting some

surprisingly good paintings. The overall tendency was sadness and loneliness but nobody noticed Vincent's alarms and

his hope for the better was rapidly fading away. His mood

could change rapidly up and down.. Vincent could analyse his

situation with

logic and he could put it all together: the

disappointments, the treaths,

the sufferings, the loneliness.... He made his conclusions

all by

himself alone and in complete lucidety...

Seriously and secretly he started preparing his

"departure from life", looking

for a suitable place to terminate this torture: maybe

behind the castle,

maybe just in his beloved wheatfield....

Never had he felt the urge "to leave this life" so strongly. Yes, in the early years he would eat paint and drink turpentine to

attract attention.

But this time it was different.... he was getting convinced about "his

departure". He started to paint secretly hidden hints to his problems and even to "death"..

Vincents ability to paint beautiful art depended on his state of mind

and his social tranquility. In the asylum in Saint Remy,

separated from

social disturbancies, van Gogh made his best works. However, now in Auvers, there were lots of derailing influences that he had to

overcome to reach an acceptable artistic level... In Arles he had had the strong hope of having his

"illusion Studio of the South" while he had the girls

in this big town... Than came Paul Gauguin with the disasterous

outcome as this guy was an egocentric artist and not a suitable

socially caring person that Vincent needed. After only two months this resulted in a

cut-off ear and Vincent going to an asylum. Vincent stayed a full year in Saint-Paul Asylum in Saint-Rémy de

Provence where his social force didn't improve while he appeared

to recover from the mental blow of the departure of

Gauguin.

Anyway he left Saint Rémy in May 1890 but the entry into the real

world

after one year in relative isolation turned

out to be

far too overwhelming for this over-sensitive vulnerable

creature....

In Paris he was happy to see Theo's son Vincent for the

first time.

However, the social intensity in Paris got, after only two

days, too much to bear and he had an early escape from Paris to

Auvers-sur-Oise, where he was planned to stay "under guidance" of

Paul Gachet, a homeopathic doctor and art-collectioner. Gachet, himself a

complex and busy personality, never digged deep into the

psyche of Vincent nor gave him any relaxing herbs...

Gachet put him up to

simply paint. Vincent anyway felt some kind of help and friendship

while he was trying to find an equilibrium in his mind while painting some

surprisingly good paintings. The overall tendency was sadness and loneliness but nobody noticed Vincent's alarms and

his hope for the better was rapidly fading away. His mood

could change rapidly up and down.. Vincent could analyse his

situation with

logic and he could put it all together: the

disappointments, the treaths,

the sufferings, the loneliness.... He made his conclusions

all by

himself alone and in complete lucidety...

Seriously and secretly he started preparing his

"departure from life", looking

for a suitable place to terminate this torture: maybe

behind the castle,

maybe just in his beloved wheatfield....

Never had he felt the urge "to leave this life" so strongly. Yes, in the early years he would eat paint and drink turpentine to

attract attention.

But this time it was different.... he was getting convinced about "his

departure". He started to paint secretly hidden hints to his problems and even to "death"..

Ten indicative paintings |

He painted these harbingers in the two months before his suicide and one can see the development of Vincent's sad and lonely mind into a suicidal state, resulting in the last painting here below: "TreeRoots" is his final suicide note. On that fatal day and after he almost terminated this big canvas, Vincent walked into the field and shot himself... Here below the sequence from worrying to finally deadly....

#1

|

In mid-June 1890, Auvers, Vincent painted "The White House"... a frigthening house of witches and strange windows. Was it a brothel maybe? The only words Vincent wrote to Theo were: "The second study, a white house in the verdure with a star in the night sky and an orange-coloured light in the window and black verdure and a note of sombre pink."

"The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg/Russia

writes on www:

In May 1890, Vincent van Gogh came to Auvers-sur-Oise and

painted

a series of pictures with houses. The Auvers period began

with the hope

of a new life and the recovery of health. This sense of

hope was

expressed in the pictures executed in May. In the June

paintings, the

motif of the home remained at the centre of the artist's

attention, but

its emotional range expanded greatly - from gloomy

foreboding to

conciliation. Since the emotion was expressed by the

artist not through

the subject itself, but through his manipulation of the

methods of

painting, the structure of his compositions changed each

time. In the

present picture a frozen quality prevails, and the chief

lines are stable

horizontals and verticals. They are needed to draw a

house, but they

can turn it into a prison. The artist gives much attention

to windows,

the "eyes" of a home. The red splashes of the windows to

the right are

alarming; van Gogh would draw a star, a sign of fate, at

moments of

greatest anguish. The White House at Night expresses the

great

psychological tension under which Van Gogh found himself.

"The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg/Russia

writes on www:

In May 1890, Vincent van Gogh came to Auvers-sur-Oise and

painted

a series of pictures with houses. The Auvers period began

with the hope

of a new life and the recovery of health. This sense of

hope was

expressed in the pictures executed in May. In the June

paintings, the

motif of the home remained at the centre of the artist's

attention, but

its emotional range expanded greatly - from gloomy

foreboding to

conciliation. Since the emotion was expressed by the

artist not through

the subject itself, but through his manipulation of the

methods of

painting, the structure of his compositions changed each

time. In the

present picture a frozen quality prevails, and the chief

lines are stable

horizontals and verticals. They are needed to draw a

house, but they

can turn it into a prison. The artist gives much attention

to windows,

the "eyes" of a home. The red splashes of the windows to

the right are

alarming; van Gogh would draw a star, a sign of fate, at

moments of

greatest anguish. The White House at Night expresses the

great

psychological tension under which Van Gogh found himself.

#2 |

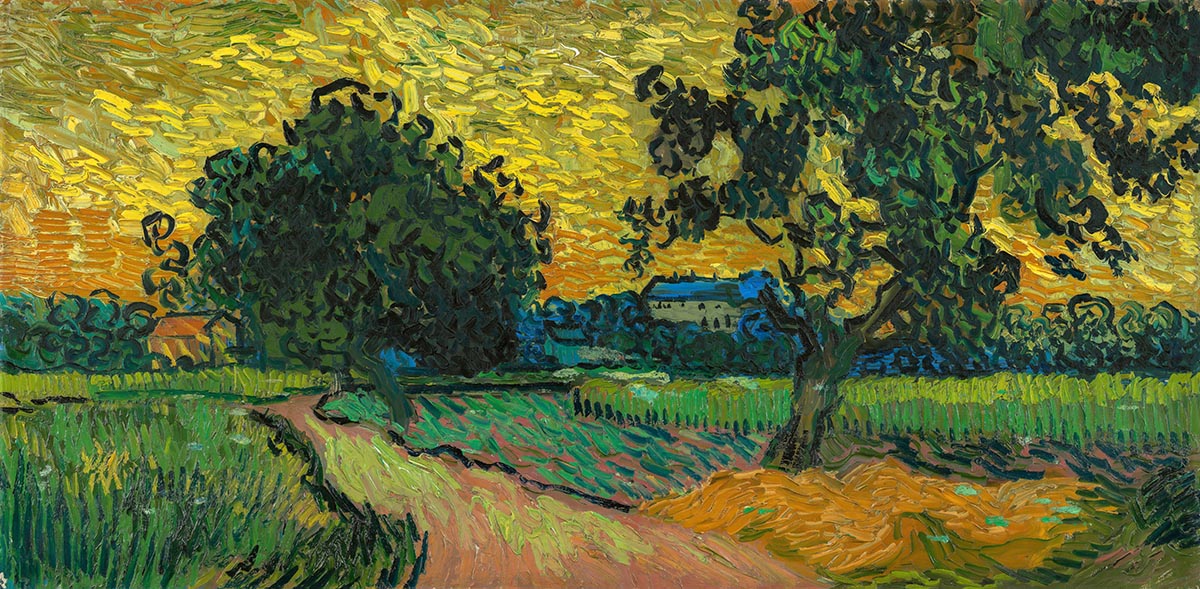

As well in June 1890 Vincent painted "Twilight behind the

castle", a 100x50cm

work showing an area of Auvers where he would execute his

suicide a month later.... He was exploring Auvers in search for a

good suicide location.

He didn't tell not even his brother Theo... Only he wrote

him in a letter:

“An evening effect—two completely dark pear trees against

yellowing sky with

wheatfields, and in the violet background the château

encased in the somber

dark greenery.”

Here the comment on the website of van Gogh Museum

Amsterdam mentioning

"brushstrokes" and ignoring the stress of the painter

being here behind the castle

and planning his suicide. Quote of the museum

website: "Van Gogh made this

evening landscape in the fields near Auvers, with a view

of the local castle.

He rendered the tangled black branches of the pear trees

with a flurry of black

brushstrokes. This reinforces the contrast between the

dark trees and the

luminous yellow sky."

Martin Bailey in Finale: "But what gives the

picture its impact is the luminous,

golden evening sky. Van Gogh was aiming not for realism,

but for dramatic

effect. Landscape

at Twilight has a particular resonance in the van

Gogh story,

since Vincent shot himself on the edge of a wheatfield

that layed just beyond the

far side of the château. In the early evening of 27 July

1890, when he set off

for his last journey, he probably walked along the very

path that appears in this

painting. But for once, it was not art that was on his

mind—his agonising

thoughts were on the impending end."

#3

|

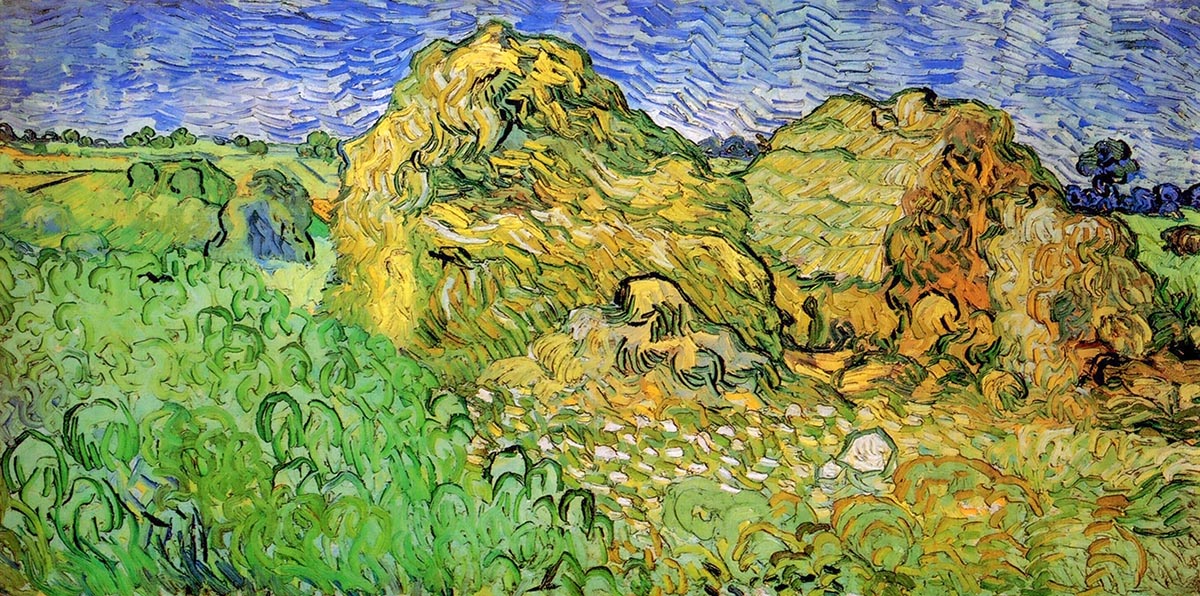

Considered one of van Gogh’s very last paintings, Field

with Stacks of Wheat is

both more rigid and at the same time more abstract than

Wheatfield with

cornflowers. Divided into fields of varying rhythmical

structure, the brushstrokes

here overlie the landscape like a grid. The picture

culminates in the two large

stacks of wheat that tower over the empty plateau like

abandoned dwellings and

thereby almost completely cut off the sky. The only living

creature is a solitary

crow, flying into the depths of the landscape on the left.

Considered one of van Gogh’s very last paintings, Field

with Stacks of Wheat is

both more rigid and at the same time more abstract than

Wheatfield with

cornflowers. Divided into fields of varying rhythmical

structure, the brushstrokes

here overlie the landscape like a grid. The picture

culminates in the two large

stacks of wheat that tower over the empty plateau like

abandoned dwellings and

thereby almost completely cut off the sky. The only living

creature is a solitary

crow, flying into the depths of the landscape on the left.

#4

|

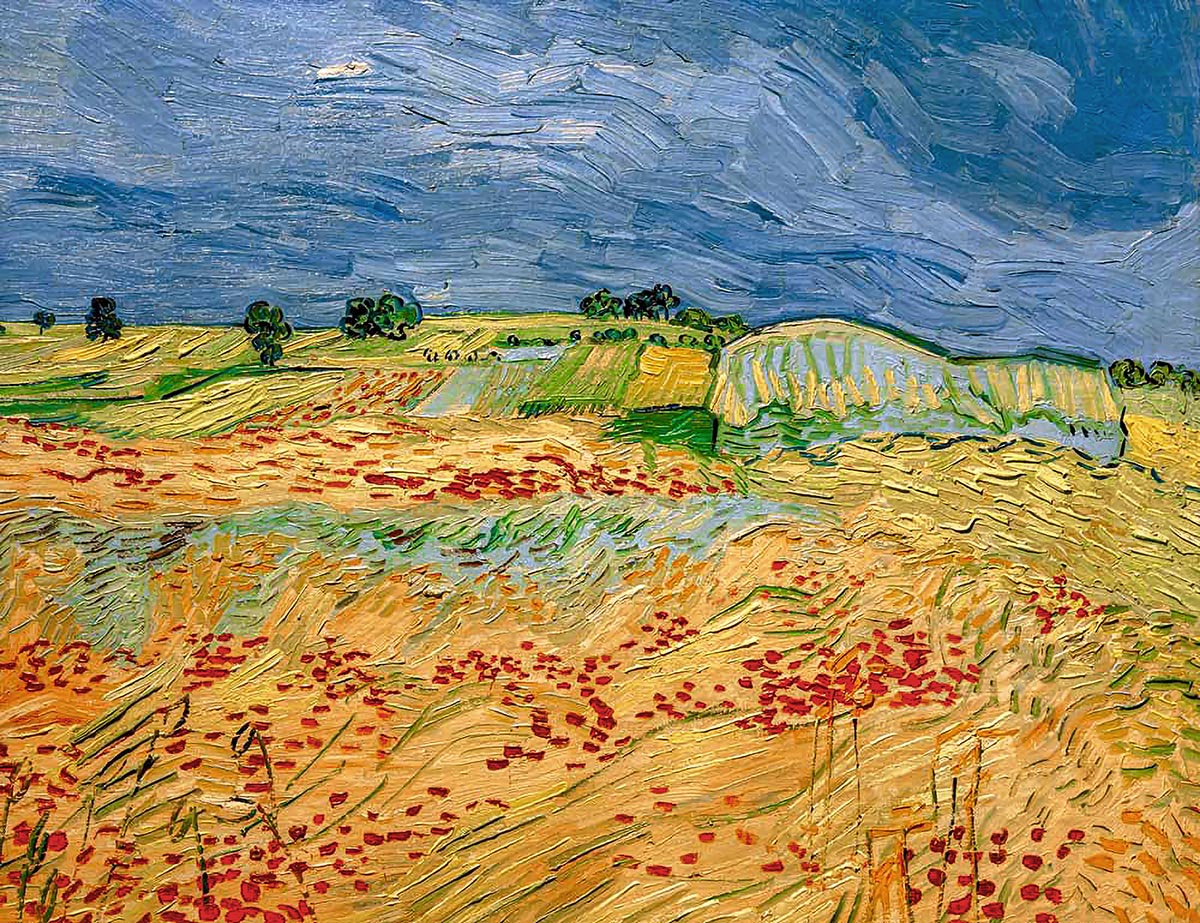

The area surrounding Auvers afforded van Gogh plenty of

scenery for inspiration,

and during his last months, the artist painted numerous

scenes of wheat fields

and wide-open, windy countryside. The sky here has an

oppressive weight, and

seems to bear down on the vast expanse of land, while both

the sky and the

land have been pointed with on undulating rhythm that

suggests great movement

the picture has an uneasiness, which is compounded by

peculiar perspective.

The field delineated to the right of the picture appears

to jump forward, while

those to the left that should be on the same rush

backwards, and there is a

spatial ambiguity between the area of poppies in the

foreground and the fields

in the distance. The whole presents a turbulent image that

is unsettling and

unconvincing. The painting was done in the weeks prior to

him taking his own

life, and at a time when his world was falling in. He was

extremely anxious

about his brother Theo and his family, and had fallen out

with Dr Gachet -

he felt alone and ultimately unable to cope.

The area surrounding Auvers afforded van Gogh plenty of

scenery for inspiration,

and during his last months, the artist painted numerous

scenes of wheat fields

and wide-open, windy countryside. The sky here has an

oppressive weight, and

seems to bear down on the vast expanse of land, while both

the sky and the

land have been pointed with on undulating rhythm that

suggests great movement

the picture has an uneasiness, which is compounded by

peculiar perspective.

The field delineated to the right of the picture appears

to jump forward, while

those to the left that should be on the same rush

backwards, and there is a

spatial ambiguity between the area of poppies in the

foreground and the fields

in the distance. The whole presents a turbulent image that

is unsettling and

unconvincing. The painting was done in the weeks prior to

him taking his own

life, and at a time when his world was falling in. He was

extremely anxious

about his brother Theo and his family, and had fallen out

with Dr Gachet -

he felt alone and ultimately unable to cope.

#5 |

In van Gogh's "Wheatfields Under

Thunderclouds" (also called Wheat Fields

Under

Clouded Sky he depicts the loneliness of the

countryside and the degree to

which it was "healthy and heartening."

Oil on canvas, 50.4 cm x 101.3 cm. In the last weeks of

his life, van Gogh

completed a number of impressive paintings of the

wheatfields around Auvers.

This outspread field under a dark sky is one of them. In

these landscapes he

tried to express 'sadness and extreme loneliness'. But the

overwhelming emotions

that van Gogh experienced in nature were also positive. He

wrote to his brother

Theo, "I'd almost believe that these canvases will tell

you what I can't say in

words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the

countryside."

The elongated format of Wheatfields under

Thunderclouds is unusual. It

emphasizes the grandeur of the landscape, as does the

simple composition:

two horizontal planes.

In van Gogh's "Wheatfields Under

Thunderclouds" (also called Wheat Fields

Under

Clouded Sky he depicts the loneliness of the

countryside and the degree to

which it was "healthy and heartening."

Oil on canvas, 50.4 cm x 101.3 cm. In the last weeks of

his life, van Gogh

completed a number of impressive paintings of the

wheatfields around Auvers.

This outspread field under a dark sky is one of them. In

these landscapes he

tried to express 'sadness and extreme loneliness'. But the

overwhelming emotions

that van Gogh experienced in nature were also positive. He

wrote to his brother

Theo, "I'd almost believe that these canvases will tell

you what I can't say in

words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the

countryside."

The elongated format of Wheatfields under

Thunderclouds is unusual. It

emphasizes the grandeur of the landscape, as does the

simple composition:

two horizontal planes.

#6

|

The Wheatfield with Crows was made in July 1890, in the

last weeks of Van Gogh's life and many have claimed

it was his last work.

Van Gogh Museum A'dam, the ultimate authority, declared

Tree-Roots was

his last painting. Wheatfield with Crows, made on

an elongated canvas, depicts a

dramatic cloudy sky filled with crows over a wheat field.

The wind-swept wheat

field fills two thirds of the canvas. An empty path pulls

the audience into the

painting. Of making the painting van Gogh wrote that he

did not have a hard

time depicting the sadness and emptiness of the painting,

which was powerfully

offset by the restorative nature of the countryside. Ericson, cautious of attributing stylistic changes in his work to mental illness, finds the painting expresses both the sorrow and the sense of his life coming to an end.

The crows, used by van Gogh as symbol of death and rebirth

or resurrection,

visually draw the spectator into the painting.

The Wheatfield with Crows was made in July 1890, in the

last weeks of Van Gogh's life and many have claimed

it was his last work.

Van Gogh Museum A'dam, the ultimate authority, declared

Tree-Roots was

his last painting. Wheatfield with Crows, made on

an elongated canvas, depicts a

dramatic cloudy sky filled with crows over a wheat field.

The wind-swept wheat

field fills two thirds of the canvas. An empty path pulls

the audience into the

painting. Of making the painting van Gogh wrote that he

did not have a hard

time depicting the sadness and emptiness of the painting,

which was powerfully

offset by the restorative nature of the countryside. Ericson, cautious of attributing stylistic changes in his work to mental illness, finds the painting expresses both the sorrow and the sense of his life coming to an end.

The crows, used by van Gogh as symbol of death and rebirth

or resurrection,

visually draw the spectator into the painting.

#7 |

Contradicting the interpretation of Museum Toledo here

below, we believe that

we see a reaper with two (2) reaping-hooks in both of his

hands. It seems to

be Vincent on his way to heaven with in the distance a rare white field and the clouds in the sky waiting to take him up to heaven. In the field we see a guard of honor on both sides of the lane escorting Vincent in

military colors.

Toledo Museum of Art in USA just writes on their web-site:

"Vincent van Gogh was fascinated by the vast fields of wheat that stretched above Auvers-sur-Oise, a town north of Paris where he lived the last two months of his life. He painted many views of these fields,

including this landscape with a reaper cutting the golden grain while the stacked sheaves recede toward a village and the distant blue hills. For van Gogh, the reaper was sometimes a biblical metaphor of the final harvest when mankind will be reaped like ripe wheat. “But,” he wrote to his brother Theo in 1889,

“there’s nothing sad in this death, it goes its way in broad daylight with a sun

flooding everything with a light of pure gold… It is an image of death as the great

book of nature speaks

of it.”

Though inspired by the observation of his immediate surroundings, van Gogh

was not interested in mimicking what he saw. As he wrote in 1888 to Theo: “Instead of trying to reproduce exactly what I have before my eyes, I use

color more arbitrarily, to express myself more

forcibly." His thick, sculptural brushstrokes add to this forceful expression.

Toledo Museum of Art in USA just writes on their web-site:

"Vincent van Gogh was fascinated by the vast fields of wheat that stretched above Auvers-sur-Oise, a town north of Paris where he lived the last two months of his life. He painted many views of these fields,

including this landscape with a reaper cutting the golden grain while the stacked sheaves recede toward a village and the distant blue hills. For van Gogh, the reaper was sometimes a biblical metaphor of the final harvest when mankind will be reaped like ripe wheat. “But,” he wrote to his brother Theo in 1889,

“there’s nothing sad in this death, it goes its way in broad daylight with a sun

flooding everything with a light of pure gold… It is an image of death as the great

book of nature speaks

of it.”

Though inspired by the observation of his immediate surroundings, van Gogh

was not interested in mimicking what he saw. As he wrote in 1888 to Theo: “Instead of trying to reproduce exactly what I have before my eyes, I use

color more arbitrarily, to express myself more

forcibly." His thick, sculptural brushstrokes add to this forceful expression.

#8 |

Here we see a death-head overlooking the very field where

Vincent would

shoot himself in the chest in the early evening of the

27th July 1890.

Early 2021 we discovered a never noticed hidden

deaths-head by Vincent van

Gogh, while for over 130 years "hidden" in the trees. Around June 2021 we informed Van Gogh Museum A'dam about our finding, and

haven't heard back

from them yet. Vincent painted this skull just before his suicide in a painting that was long time

thought to be a "fake-vanGogh". The painting was downgraded in the 1970s, banished to the stores, dismissed as “a pastiche by an

unknown hand”. But

research by the Van Gogh Museum, the ultimate referee,

confirmed its

authenticity in 2016. Our skull is overlooking the very

wheatfield where the

shooting would happen a few weeks later. Neither scholars

of van Gogh

Museum A'dam nor the owners of the painting, the Rhode

Island Museum,

ever mentioned these skull-like brushstrokes. RSID wrote to us that they

have never published anything about these "skull-like

brush-strokes".

My opinion: "This skull is the only direct hint to his "death"

that Vincent painted in the last

years of his life." Vincent must have been surprised of

himself, painting this

first strong explicit hint to death. He must have been more and more convinced of his suicide about two weeks before

execution... He was

from the south of the Netherlands and a champion in vague

hints.... and

there were plenty in his paintings and in his letters: the

hundreds of black

crows, lots of reapers, the black cat, the rainy

landscapes, and all

Vincent's expressions of loneliness, sadness, feelings of

failure and

"the need to end his life".

However.... this death-head was very direct!!!

Early 2021 we discovered a never noticed hidden

deaths-head by Vincent van

Gogh, while for over 130 years "hidden" in the trees. Around June 2021 we informed Van Gogh Museum A'dam about our finding, and

haven't heard back

from them yet. Vincent painted this skull just before his suicide in a painting that was long time

thought to be a "fake-vanGogh". The painting was downgraded in the 1970s, banished to the stores, dismissed as “a pastiche by an

unknown hand”. But

research by the Van Gogh Museum, the ultimate referee,

confirmed its

authenticity in 2016. Our skull is overlooking the very

wheatfield where the

shooting would happen a few weeks later. Neither scholars

of van Gogh

Museum A'dam nor the owners of the painting, the Rhode

Island Museum,

ever mentioned these skull-like brushstrokes. RSID wrote to us that they

have never published anything about these "skull-like

brush-strokes".

My opinion: "This skull is the only direct hint to his "death"

that Vincent painted in the last

years of his life." Vincent must have been surprised of

himself, painting this

first strong explicit hint to death. He must have been more and more convinced of his suicide about two weeks before

execution... He was

from the south of the Netherlands and a champion in vague

hints.... and

there were plenty in his paintings and in his letters: the

hundreds of black

crows, lots of reapers, the black cat, the rainy

landscapes, and all

Vincent's expressions of loneliness, sadness, feelings of

failure and

"the need to end his life".

However.... this death-head was very direct!!!

#9 |

Emotional turmoil

Illness had struck Theo's baby, Vincent and Theo had

health problems and

employment issues. Theo was considering leaving his

employer to start his own

business. Gachet, said to have his own eccentricities

and neurosis, caused van

Gogh to write: "Now when one blind man leads another

blind man, don't they

both end up in the ditch?" After visiting Paris for a

family conference, van Gogh

returned to Auvers feeling more bleak. In a letter he

wrote, "And the prospect

grows darker, I see no future at all."

He later had a period where he said that "the trouble I

had in my head has

considerably calmed... I am completely absorbed in that

immense plain

covered with fields of wheat against the hills boundless

as the sea in delicate

colors of yellow and green, the pale violet of the

plowed and weeded earth

checkered at regular intervals with the green of the

flowering potato plants,

everything under a sky of delicate blue, white, pink,

and violet. I am almost

too calm, a state that is necessary to paint all that."

Emotional turmoil

Illness had struck Theo's baby, Vincent and Theo had

health problems and

employment issues. Theo was considering leaving his

employer to start his own

business. Gachet, said to have his own eccentricities

and neurosis, caused van

Gogh to write: "Now when one blind man leads another

blind man, don't they

both end up in the ditch?" After visiting Paris for a

family conference, van Gogh

returned to Auvers feeling more bleak. In a letter he

wrote, "And the prospect

grows darker, I see no future at all."

He later had a period where he said that "the trouble I

had in my head has

considerably calmed... I am completely absorbed in that

immense plain

covered with fields of wheat against the hills boundless

as the sea in delicate

colors of yellow and green, the pale violet of the

plowed and weeded earth

checkered at regular intervals with the green of the

flowering potato plants,

everything under a sky of delicate blue, white, pink,

and violet. I am almost

too calm, a state that is necessary to paint all that."

Four days after completing Wheat Fields after the

Rain he shot himself in

the Auvers wheat fields. Van Gogh died on July 29, 1890.

#10 |

Did the suicidal genius Vincent paint his own dead body laying between treeroots. We believe so... His suicide-plan must have been all the time (un)concious in his alert mind that day and his prefered and chosen field of execution was nearby and almost next to the location of the treeroots. Look good at the painting and please compare with the photo of 1905. The common van Gogh-style would be: discreetly disguise any dead corps in the painting to provoke nobody... And that's exactly what Vincent did. With thoughtful and controlled expressive brushstrokes he painted this blue figure: it could be a simple treeroot or ...it could be ...a dead Vincent ... Scholars together with dendrologists should compare the two existing photos (both 1905) of the real original treeroots with van Gogh's creation: "TreeRoots" (1890). The wiser men should then conclude if Vincent modified the real roots into "His TreeRoots", with a dead Vincent. Will there be a clear answer and could this painting be his final painted suicide note? Proof by contradiction.... Vincent must have been fully aware of his plans to commit suicide.... Vincent was painting his suicide-note.. He must have been painting a corps...laying between the roots....

Vincent van Gogh’s final painting, TreeRoots, is a jumble of

color and shapes:

knotted blue roots protrude from an abstract, sloping

hillside, and bright green

leaves seem to wave in the breeze. As Andries Bonger,

brother-in-law of

Vincent’s brother Theo, later wrote, “The morning before

[van Gogh’s] death,

he had painted a sous-bois (forest scene) full

of sun and life.”

Historians know that the troubled Dutch artist worked

on the canvas on July 27... the same day he returned to his hotel in

Auvers-sur-Oise, France, with a gunshot wound to the stomach. Two days later, van Gogh

died, leaving his TreeRoots unfinished. Now, thanks to a chance

encounter with a vintage

French postcard, researcher Wouter

van der Veen has discovered the exact

patch of road where van Gogh produced his last work.

Experts from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam have

corroborated the findings as “highly plausible,” according to a statement.

Van der Veen, scientific director of the Van Gogh Institute in France, made the discovery while studying a trove of early 20th-century

postcards of

Auvers that he’d borrowed from a prolific collector,

reports Nina Siegal for

the New York Times. One day, he

looked at a card from 1905 and did a

double take, sure that he’d seen the roots pictured

before.

The postcard:

And a photo around year 1905...

Vincent painted the "TreeRoots" during that fatal day July

27th

and just before his suicide attempt. Now, based on the newly-discovered location of the painting, experts say that the light in the painting is characteristic of the day's end, meaning

that van Gogh worked until an hour or two before his suicide. According to van der Veen, this is enough to say that the artist's suicide was not a mindless act. "He was working on a

complex subject, which required his full attention. He wasn't

getting drunk, or in a fit of madness," said van der Veen. "On the contrary, he

was working on a painting on the theme of life and death".

This painting should be his final suicide note....

Two recent photoos of the present treeroots, and BOTH do

not

resemble Vincents painting. So... it is time to consult a

dendrologist!

With Jo’s note: This letter, evidently his penultimate one to Theo, was found on Vincent’s body after his suicide on the27th. There is a note in Theo’s handwriting on it: “Letter found on him on July 29."

Auvers, 23 July 1890.

My dear brother,

Thanks for your kind letter and for the 50 fr. note it contained

There are many things I should like to write you about, but I feel it is pointless. I hope you have found these gentlemen favorably disposed toward you.

Your reassuring me as to the state of peace of your household was not worth the trouble, I think, having seen the other side of it for myself. And I quite agree with you that rearing a boy on a fourth floor is a hell of a job for you as well as Jo.

Since it is going well, which is the main thing, I should insist on things of less importance. My word, before we have a chance of talking business more calmly, there is probably a long way to go.That is all I want to say, that I noted it with a certain fright and I cannot hide it. But that is all there is to it.

The other painters, whatever they think of it, instinctively keep themselves at a distance from discussions about actual trade.

Well, the truth is, we cannot speak other than by our paintings. But still, my dear brother, there is this that I have always told you, and I repeat it once more with all the earnestness that can be imparted by an effort of a mind diligently fixed on trying to do as well as one can - I tell you again that I shall always consider that you are something other than a simple dealer in Corots, that through my mediation you have your part in the actual production of some canvases, which even in the cataclysm retain their calm.

For this is what we have got to, and this is all or at least the chief thing that I can have to tell you at a moment of comparative crisis. At a moment when things are very strained between dealers in paintings by dead artists, and living artists.

Well, my work to me, I risk my life on it, and my reason has half foundered - all right - but you are not one of those dealers in men, as far as I know, and you can take sides, I find, truly acting with humanity, but what is the use?

And yet, one of the main messages of the scholars is that van Gogh wasn't the crazed visionary whose work was fuelled by the fire of his madness, as was wrongly depicted after his death. In fact, his brilliant paintings were created in spite of his illness... “When he was really ill he couldn’t paint."

Future confirmation of the relevance of our skull-like brushstrokes by the scientists could further assure the theory of Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam and the scholars, that Vincent indeed committed a planned suicide and that he wasn't murdered as suggested in some publications.

Dr. Gachet: A few hours after the shooting, Vincent’s doctor, Paul Gachet, wrote to the artist’s brother, Theo van Gogh, to break the news that “he has wounded himself”. Dr. Gachet had inspected the wound and spoken with Vincent. Had there been anything to suggest possible foul play, he would presumably not have let the matter rest. Two weeks after Vincent’s death, he wrote again to Theo, explicitly using the word “suicide”.

Theo: Theo, who rushed to his brother’s bedside and conversed with him during his final 12 hours, was convinced it was suicide. Three days after Vincent’s death, he wrote an emotionally charged letter to his wife Jo: “One of his last words was: this is how I wanted to go; it took a few moments; then it was over; he found the peace he hadn’t been able to find on earth.” Had Theo any reason to believe his beloved brother might have been shot by someone else, he would surely have informed the police.

Friends: Emile Bernard, Van Gogh’s closest friend, attended the funeral and spoke with Dr Gachet and Theo. Dr. Gachet told Bernard that he had hoped to save his patient’s life, but Vincent had warned him that “then I’ll have to do it over again”. Two days after the funeral, Bernard wrote a detailed account to the critic Albert Aurier: “He killed himself. On Sunday evening he went into the countryside around Auvers, placed his easel against a haystack and went behind the château and fired a vrevolver shot at himself.” Vincent had “done it in complete lucidity”, with a “wish to die”.

Paul Gaugain: In Gauguin’s memoir "Avant et Après": he wrote that “van Gogh shot himself in the stomach”. Although Gauguin was in Brittany at the time, he remained in touch with Vincent’s circle of friends. Gauguin knew van Gogh well from their time together in the Yellow House in Arles, where their collaboration had come to an abrupt end with the ear incident, and he was only too aware of his friend’s fragile mental condition.

Police: No police records about the shooting survive, but Bernard also informed Aurier that the innkeeper, Arthur Ravoux, had told him about “the gendarmes who came to his bed to reproach him for an act for which he was responsible”. His daughter, Adeline Ravoux (who was 13 at the time of the incident), later reported that her father had often spoken about van Gogh. The artist had told the police: “What I have done is nobody else’s business. I am free to do what I like with my own body.” Surely the police would have followed up if they had harbored any suspicions of foul play. Adeline even named one of the gendarmes as Rigaumont.

The church: The church believed it was suicide. Henri Tessier, the Catholic priest in Auvers, refused to allow the funeral service to be held in his church, or to provide the parish hearse to carry Van Gogh’s body to the cemetery. Tessier was presumably concerned that the Protestant artist had sinned by committing suicide. Theo then needed to amend the printed funeral invitations.

The gun. The recent emergence of the gun is further

evidence for suicide. The corroded gun that is said to have killed van

Gogh was displayed and auctioned in Paris in June, fetching €162,500. It

had been found around 1960 by a farmer, abandoned in a field in the area where the artist is believed to have suffered the wound. If it

is the van Gogh gun, which is very likely (although not certain), then it's discovery near the surface of the ground suggests it was abandoned rather than hidden. If it was Secrétan who had fired the fatal shot, then surely he would have hidden the weapon properly, perhaps by burying it more deeply or throwing it in the nearby river Oise. He would have fired more shots to silence Vincent forever. But if van Gogh had pulled the trigger, he would have immediately fallen, dropping the gun.

The gun. The recent emergence of the gun is further

evidence for suicide. The corroded gun that is said to have killed van

Gogh was displayed and auctioned in Paris in June, fetching €162,500. It

had been found around 1960 by a farmer, abandoned in a field in the area where the artist is believed to have suffered the wound. If it

is the van Gogh gun, which is very likely (although not certain), then it's discovery near the surface of the ground suggests it was abandoned rather than hidden. If it was Secrétan who had fired the fatal shot, then surely he would have hidden the weapon properly, perhaps by burying it more deeply or throwing it in the nearby river Oise. He would have fired more shots to silence Vincent forever. But if van Gogh had pulled the trigger, he would have immediately fallen, dropping the gun.

This painting "View at Auvers with Church" was made about a week before the suicide and is definitely pointing towards "death in the cornfield". It cannot be "a secret message" to these two local boys: "Please kill me here in this field". And for Vincent, it would be a shear impossible job in this small french village Auvers, to secretly organize the two drunken boys and the loaded gun, and all this at the right time and at the right specific location. And during all this hassle Vincent had to paint his suicide note, the 50x100cm huge ultimate masterpiece: "TreeRoots"...

This painting "View at Auvers with Church" was made about a week before the suicide and is definitely pointing towards "death in the cornfield". It cannot be "a secret message" to these two local boys: "Please kill me here in this field". And for Vincent, it would be a shear impossible job in this small french village Auvers, to secretly organize the two drunken boys and the loaded gun, and all this at the right time and at the right specific location. And during all this hassle Vincent had to paint his suicide note, the 50x100cm huge ultimate masterpiece: "TreeRoots"...

René Secrétan. The purported killer, never confessed and indeed claimed he had left Auvers before the shooting The only occasion on which Secrétan publicly spoke about van Gogh was in an interview published in 1957, when he was aged 82. This was just a few months before his death. Secrétan never said he fired the shot, instead of saying Vincent had somehow got hold of a gun, which had been in the young man's possession. Secrétan also had an apparent alibi, since he claimed to have left Auvers some days before the shooting. Although there is no way of verifying his statements, in my mind there is nothing in the interview which represents prima facie evidence that he might have been guilty of murder or manslaughter. In any case, it must be extremely rare for a victim fatallyb injured in a shooting by someone else to claim it was actually a suicide attempt. To add to the implausibility, why should Secrétan, if guilty, have voluntarily given an interview about van Gogh nearly 70 years afterwards, at a time when he was under no suspicion?

Vincent had painted

again

and again his "wheatfield

of execution" in front of the village Auvers in

those

weeks before his suicide.

He was more and more

convinced on his choice

for the location of the

execution of his suicide.

Here You can see

the very cornfield where

it had to happen....

Vincent had painted

again

and again his "wheatfield

of execution" in front of the village Auvers in

those

weeks before his suicide.

He was more and more

convinced on his choice

for the location of the

execution of his suicide.

Here You can see

the very cornfield where

it had to happen....

The key-people at the time believed Vincent van Gogh had shot himself. Suicide was then condemned by the Catholic church and regarded by society as wrong. Had Vincent’s family and friends had any suspicions that someone else was responsible, they surely would have voiced their concerns. And why point the finger at Secrétan? The only substantive information on his links with van Gogh comes from his 1957 interview, in which he said nothing to suggest he was guilty of murder. What would be useful in determining whether it was suicide or murder would be forensic evidence about the nature of the wound, but there is little information. Dr. Gachet, who died in 1909, never spoke out about the wound during his lifetime, and the descriptions, given after his death by his son were very brief (on the color of the skin on the adjacent skin, its location on the body and the angle of the shot) and these details have recently been subject to different interpretations.

Vincent had tried to kill himself a year before.

In April 1889, four months after mutilating his ear, Vincent had written to

Theo: “If I was without your friendship I would be sent back without remorse to

suicide, and however cowardly I am, I would end up going there.” A few

months later he tried to poison himself by eating his paints and turpentine,

but fortunatel his doctor saved him. A few days after his recovery, Dr.

Théophile Peyron told Theo that Vincent’s “ideas of suicide have disappeared”.

Vincent himself reported that “I’m trying to get better now like someone who,

having wanted to commit suicide, finding the water too cold, tries to

catch hold of the bank again”. He was undoubtedly a vulnerable individual.

Vincent faced a difficult time in the final months of his life: In

May 1890, after a year in the asylum just outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence,

Vincent moved north, to the village of Auvers. Throughout his career,

Theo had been his closest confidante and had provided a regular financial

allowance. But Theo, an art dealer in Paris, had recently married and then

had a son in January 1890. Vincent was therefore concerned that a wife

and an infant would mean he might lose much of his brother’s emotional

and financial support. He was also worried about Theo’s recent problems at

work with the owners of the gallery. Although most of the time

Vincent could cope with the challenges of his life, he was upset.

Meanwhile: Theo recognised that Vincent was experiencing problems. In a letter dated 22 July, he wrote, "I hope, my dear Vincent, that your health is good, and since you say that you write with difficulty, and don't talk about your work I am a little afraid that there is something troubling you or not going right."

The painter was also exhausted from working hard in the weeks before that fatal day, the 27th of July 1890, and the high standards he set for himself. He was uncertain about the future and felt that he had failed, as a man and as an artist.

We, therefore, have to make a judgment on what seems

the more likely explanation. Should we accept van Gogh’s words that

he had decided to end his life? Or does Secrétan’s

interview suggest it was he who pulled the trigger? For me, the

answer is clear. As Theo put it so poignantly: Vincent then “found the peace he hadn’t been able to find on earth”.

Vincent: "For myself, I can only say at the moment that I think we

all need rest. I feel.... I failed.... And the prospect grows

darker, I see no happy future at all."

This sad and lonely self-crucifixion was his final

decisive solution to end all his sufferings.

Vincent’s suicide has become the grand finale of the story of the martyr for art...

By the end of the day July 27th Vincent was finishing

painting the big

"TreeRoots". In the painting his dead body was laying

between the roots.

This was his suicide note..... Around 6pm he brought the easel and

the painting back to Ravoux....

and started to

finally execute his suicide-plan.

All was ready... and he was ready...

He had the loaded ready gun with him that he gotten from

the owner of

the inn, Arthur Ravoux to scare off the always annoying

crows while

he was painting.

The evening was falling and Vincent went up the hill and

in the him so

familiar cornfield that he had painted and explored all

the time .... he

walked awhile along the field, got behind the castle and

....... he .....

anxious and hesitating, shot himself in his chest and fell

to the ground.

Later in the night and when still laying in the field,

Vincent gained consciousness, and

as he confided later to Theo, tried to find the gun to finish off the job. But he could not find it as it

was getting darker.

So.... badly  wounded of the single shot

in the chest he would get down

the mountain and walk back to Ravoux-Inn. Adeline Ravoux,

the

innkeeper's daughter who was only 13 at the time, clearly

recalled

the incidents of July 1890. In an account written when she

was 76,

reinforced by her father's repeated reminders, she

explained how on

27 July, van Gogh left the inn after breakfast. When he

had not

returned by dusk, given the artist's regular habits, the

family became

worried. He finally arrived after nightfall, probably

around 9 pm, holding his stomach. Adeline's mother asked whether there was a

problem.

Van Gogh started to answer with difficulty, "No, but I

have..." as he

climbed the stairs up to his room. Her father thought he

could hear

groans and found van Gogh curled up in bed. When he asked

whether

he was ill, Vincent showed him the wound near his heart

and van Gogh

admitted he had set out for the wheatfield where he had

recently been

painting and had attempted suicide by shooting himself.

wounded of the single shot

in the chest he would get down

the mountain and walk back to Ravoux-Inn. Adeline Ravoux,

the

innkeeper's daughter who was only 13 at the time, clearly

recalled

the incidents of July 1890. In an account written when she

was 76,

reinforced by her father's repeated reminders, she

explained how on

27 July, van Gogh left the inn after breakfast. When he

had not

returned by dusk, given the artist's regular habits, the

family became

worried. He finally arrived after nightfall, probably

around 9 pm, holding his stomach. Adeline's mother asked whether there was a

problem.

Van Gogh started to answer with difficulty, "No, but I

have..." as he

climbed the stairs up to his room. Her father thought he

could hear

groans and found van Gogh curled up in bed. When he asked

whether

he was ill, Vincent showed him the wound near his heart

and van Gogh

admitted he had set out for the wheatfield where he had

recently been

painting and had attempted suicide by shooting himself.

Doctor Gachet was called upon but he considered Vincents

situation as

hopeless. Ravoux and Hirschig spent the night at van

Gogh's bedside.

The artist sometimes smoked, sometimes groaned but

remained silent

almost all night long, dozing off from time to time. The

following morning,

two gendarmes visited the inn, questioning van Gogh about

his attempted

suicide. In response, he simply replied: "My body is mine

and I am free to

do what I want with it. Do not accuse anybody, it is I

that wished to

commit suicide. As soon as the post office opened on

Monday morning,

Adeline's father sent a telegram to Vincent's brother

Theo, who

arrived from Paris by train during the afternoon. During

the afternoon

and night the two brothers talked while Vincent smoked his

pipe. Adeline

Ravoux explains how the two of them watched over van Gogh

who fell

into a coma and died at about one o'clock in the morning;

his death

certificate records the time of death as 1.30am.

In a letter to his sister Lies, Theo told of his brother's

feelings just before

his death: "He himself wanted to die. When I sat at his

bedside and said

that we would try to get him better and that we hoped that

he would

then be spared this kind of despair, he said, "La

tristesse durera toujours".

(The sadness will last forever). I understood what he

wanted to say

with those words. In her memoir of December 1913, Theo's

wife

Johanna refers first to a letter from her husband after

his arrival at

Vincent's bedside: "He was glad that I came and we are

together all

the time... Poor fellow, very little happiness fell to his

share, and no

illusions are left him. The burden grows too heavy at

times, he feels so

alone..." And after Vincent's death he wrote: "One

of his last words

was: 'I wish I could pass away like this,' and his wish

was fulfilled. A few

moments and all was over. He had found the rest he could

not find on

earth..."

Émile Bernard, an artist and friend of van Gogh, who

arrived in Auvers

on 30 July for the funeral, tells a slightly different

story, explaining that

van Gogh went out into the countryside on the Sunday

evening, "left his

easel against a haystack and went behind the château and

fired a

revolver shot at himself." He tells how van Gogh had said

that "his suicide

had been absolutely deliberate and that he had done it in

complete

lucidity... When Dr Gachet told him that he still hoped to

save

his life, van Gogh replied, 'Then I'll have to do it over

again.'"

In her memoir of December 1913, Theo's wife Johanna refers first to a letter from her husband after his arrival at Vincent's bedside: "He was glad that I came and we are together all the time... Poor fellow, very little happiness fell to his share, and no illusions are left him. The burden grows too heavy at times, he feels so alone..." And after his death, he wrote: "One of his last words was, 'I wish I could pass away like this,' and his wish was fulfilled. A few moments and all was over. He had found the rest he could not find on earth..."

Theo wrote to his wife Jo

three days later after he had spoken to Vincent

before he died: “One of his last words was: this

is how I wanted to go and it

took a few moments and then it was over and he

found the peace he hadn’t

be able to find on earth.”

Theo wrote to his wife Jo

three days later after he had spoken to Vincent

before he died: “One of his last words was: this

is how I wanted to go and it

took a few moments and then it was over and he

found the peace he hadn’t

be able to find on earth.”

The coffin was carried to the hearse at three o'clock. The

company climbed

the hill outside Auvers in hot sunshine, Theo and several

of the others

sobbing pitifully. The little cemetery with new tombstones

was on a little hill

above fields that were ripe for harvest. Dr Gachet, trying

to suppress his tears,

stammered out a few words of praise, expressing his

admiration for an

"honest man and a great artist... who had only two aims,

art and humanity."

Van Gogh was particularly productive during his last few

weeks in Auvers,

completing over 70 paintings as well as a number of

drawings and sketches.

They cover landscapes, portraits and still lifes. Some of

them appear to

reflect his increasing loneliness while many others, with

their bright colours,

convey a more positive attitude. The letters he wrote

during his last two

months offer a considerable amount of background on van

Gogh's

relentless will to paint coupled with frequent periods of

losing courage

and hope.

Vincent Van Gogh, now long departed into his own dark night, must be wondering what madness causes people to pay hundreds of millions of dollars for paintings he could not even give away during his lifetime. I cannot even imagine, as I walk among his varying depictions of dream, nightmare, love, and life, what he would have thought of this strange turn of fate.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

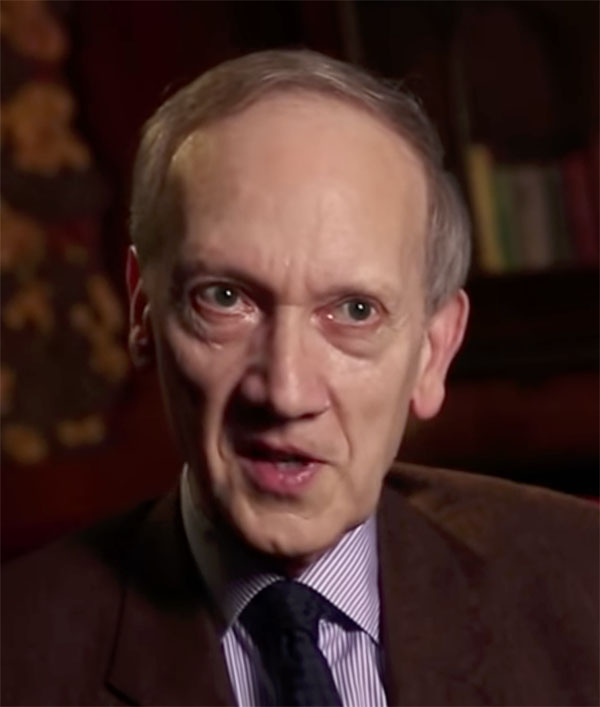

Martin Bailey confirmed van Gogh's suicide in "ART-NEWSPAPER"

Link to the article Martin

Bailey

Link to the article Martin

Bailey

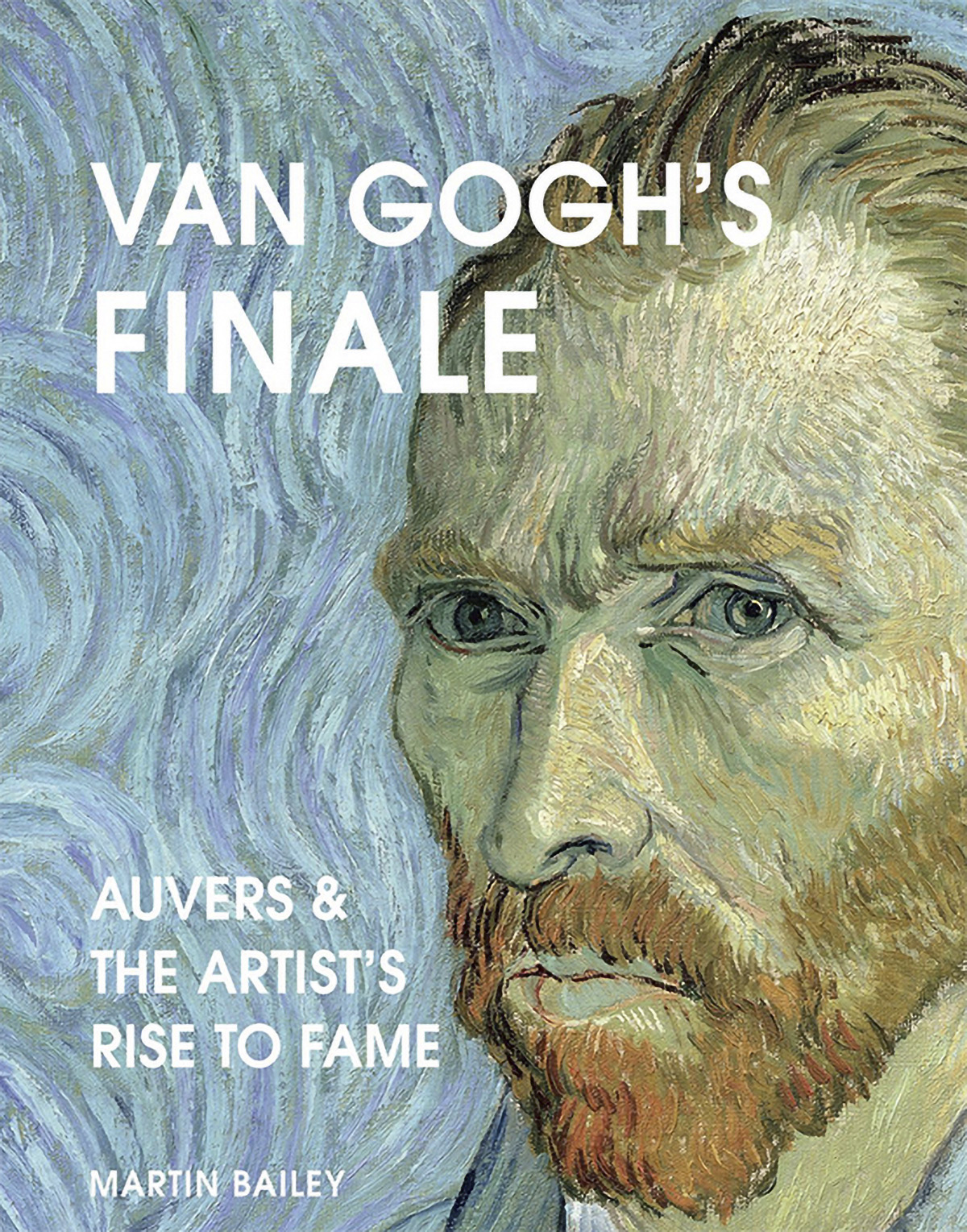

Read the full story of Vincent's

final months in a beautiful

full-color book called "FINALE",

written by Martin Bailey,

the famous "van-Gogh-connoisseur".

Copying and republishing of (parts of) this website is

only allowed with mentioning the source: www.art-aruba.com

Copyright JCvanRoekel 2021

jancvanroekel@gmail.com